Opinion: The Supreme Court isn't well. The only hope for a cure is more justices.

Click here to read on the Washington Post's website.

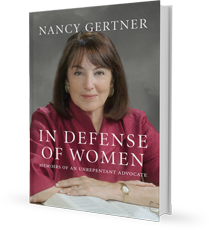

By Nancy Gertner and Laurence H. Tribe

December 9, 2021

Nancy Gertner is a retired U.S. District Court judge. Laurence H. Tribe is Carl M. Loeb University Professor emeritus and professor of constitutional law emeritus at Harvard Law School. Both served on the Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court.

We now believe that Congress must expand the size of the Supreme Court and do so as soon as possible. We did not come to this conclusion lightly.

One of us is a constitutional law scholar and frequent advocate before the Supreme Court, the other a federal judge for 17 years. After serving on the Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court over eight months, hearing multiple witnesses, reading draft upon draft of the final report issued this week, our views have evolved. We started out leaning toward term limits for Supreme Court justices but against court expansion and ended up doubtful about term limits but in favor of expanding the size of the court.

We listened carefully to the views of commissioners who disagreed. Indeed, the process was a model for how people with deeply diverging perspectives can listen to one another respectfully and revise their views through genuine dialogue. We voted to submit the final report to President Biden not because we agreed with all of it — we did not — but because it accurately reflects the complexity of the issue and that diversity of views. There has never been so comprehensive and careful a study of ways to reform the Supreme Court, the history and legality of various potential reforms, and the pluses and minuses of each. This report will be of value well beyond today’s debates.

But make no mistake: In voting to submit the report to the president neither of us cast a vote of confidence in the Supreme Court itself. Sadly, we no longer have that confidence, given three things: first, the dubious legitimacy of the way some justices were appointed; second, what Justice Sonia Sotomayor rightly called the “stench” of politics hovering over this court’s deliberations about the most contentious issues; and third, the anti-democratic, antiegalitarian direction of this court’s decisions about matters such as voting rights, gerrymandering and the corrupting effects of dark money.

Those judicial decisions haven’t been just wrong; they put the court — and, more important, our entire system of government — on a one-way trip from a defective but still hopeful democracy toward a system in which the few corruptly govern the many, something between autocracy and oligarchy. Instead of serving as a guardrail against going over that cliff, our Supreme Court has become an all-too-willing accomplice in that disaster.

Worse, measures the court has enabled will fundamentally change the court and the law for decades. They operate to entrench the power of one political party: constricting the vote, denying fair access to the ballot to people of color and other minorities, and allowing legislative district lines to be drawn that exacerbate demographic differences. As a result, the usual ebb and flow that once tended to occur with succeeding elections is stalling. A Supreme Court that has been effectively packed by one party will remain packed into the indefinite future, with serious consequences to our democracy. This is a uniquely perilous moment that demands a unique response.

None of the reforms that have been proposed precisely fit the problem that needs remedying. Term limits cannot be implemented in time to change the court’s self-reinforcing trajectory. And while much can be said in favor of the narrower repairs the commission addressed — such as increasing the transparency of the court’s proceedings, reducing its discretion over its docket or imposing constraints on its use of emergency procedures (“the shadow docket”) — none is adequate.

Offsetting the way the court has been “packed” in an antidemocratic direction with added appointments leaning the other way is the most significant clearly constitutional step that could be taken quickly. Of course, there is no guarantee that new justices would change the destructive direction of judicial doctrine we have identified; respect for judicial independence makes that impossible. Of course, successive presidents might expand the court further, absent an unattainable constitutional amendment fixing its size at a number such as 13. But the costs are worth the benefits.

Though fellow commissioners and others have voiced concern about the impact that a report implicitly criticizing the Supreme Court might have on judicial independence and thus judicial legitimacy, we do not share that concern. Far worse are the dangers that flow from ignoring the court’s real problems — of pretending conditions have not changed; of insisting improper efforts to manipulate the court’s membership have not taken place; of looking the other way when the court seeks to undo decades of precedent relied on by half the population to shape their lives just because, given the new majority, it has the votes.

Put simply: Judicial independence is necessary for judicial legitimacy but not sufficient. And judicial independence does not mean judicial impunity, the illusion of neutrality in the face of oppression, or a surface appearance of fairness that barely conceals the ugly reality of partisan manipulation.

Hand-wringing over the court’s legitimacy misses a larger issue: the legitimacy of what our union is becoming. To us, that spells a compelling need to signal that all is not well with the court, and that even if expanding it to combat what it has become would temporarily shake its authority, that risk is worth taking.